|

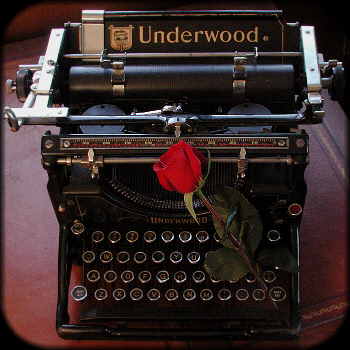

Turgid Prose

|

|

Since 1982, the English Department at San Jose State University has sponsored the prestigious Bulwer-Lytton bad writing contest [ www.bulwer-lytton.com ] in which bad writers from around the globe compete pen-to-pen in a no-commas-barred fight to create the worst possible opening sentence for a novel. For reasons that remain entirely fathomable to anyone who has perused the printed collections of winning entries (and as many others that were needed to fill out the volumes to publishable lengths), I've never won this contest myelf, but I have made several unsuccessful attempts. Now, in most cases, that would have been the end of the story for all those story beginnings, but thanks to the miracle of "personal vanity page" technology, I have rescued these non-winning attempts at literary awfulness from a fate of well-deserved oblivion. |

|

|

Trygve.Com sitemap what's new FAQs diary images exercise singles humor recipes media weblist internet companies community video/mp3 comment contact |